Discovering Clay

Potters have been digging and processing their own clay for millennia. It has only been since the Industrial Revolution, which began in the 1800s, that clay started being sold by suppliers on the market. Before that time potters situated themselves near a good source of clay and always the trade was passed down from generation to generation. In many places such as China, Korea and Great Britain whole families of potters would build small towns near a clay source and the local economy centered on pottery making.

Potters have been digging and processing their own clay for millennia. It has only been since the Industrial Revolution, which began in the 1800s, that clay started being sold by suppliers on the market. Before that time potters situated themselves near a good source of clay and always the trade was passed down from generation to generation. In many places such as China, Korea and Great Britain whole families of potters would build small towns near a clay source and the local economy centered on pottery making.

Clay is a smooth soft rock made up of mineral particles as fine as dust. Clay particles are all that remain of rocks such as feldspar after these have weathered and decomposed. Most clay remains at the site where it formed thus making a clay deposit. In its undeveloped state, it is one of the few natural resources that has no perceptible value of its own yet can be transformed into some of the most valued works of art.

Today, many potters caution that it is hardly worth the effort and time to dig your own native clay while others strongly encourage those that are able to take advantage of this abundant resource. A potter can also gain a great deal of practical experience and vastly broaden his or her knowledge by going out and digging one’s own clay and feeling the fulfillment of actually making a pot from the ground up.

Here at our shop quite a number of people ask if we use clay from the Brazos River, which borders our farm. We have been unable to utilize Brazos River clay because of a major lime contamination. A good part of this is due to the high limestone cliffs just above the river and every time it rains more limestone washes down the banks contaminating the very absorbent clay. James Chappell, author of, The Potter’s Complete Book of Clay and Glazes, says, “ While the presence of alkalies can be tolerated, the presence of lime cannot; when such clay is fired, the lime turns into calcium oxide, which will absorb water, expand inside the pot and cause it to crack, flake or chip.”

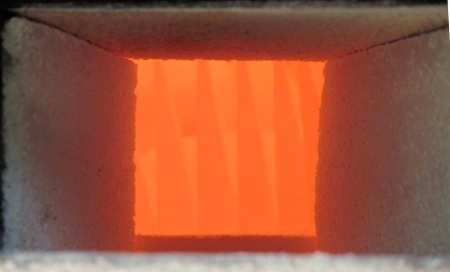

There are two basic clay bodies, earthenware and stoneware. Earthenware can only be fired up to the temperature range between 1700 degrees (F) and 2000 degrees (F). Because of this it is not waterproof and the finished product can be chipped or scratched easily. Stoneware is much less common than earthenware, yet it is highly sought after for it’s durability and lasting strength. This type of clay can be fired up to 2400 degrees (F) to become vitreous [meaning ‘like a rock’] making it water proof even when left unglazed, thus the name, stoneware.

About four miles from the Northern branch of our Ploughshare school, in Idaho, is a large deposit of kaolin called Helmer kaolin. The mineral kaolin is an extremely refractory clay with a melting point at 3200 degrees (F). It cannot be used alone as a clay body due to its highly nonplastic texture. Because of this it must be combined with other clays to increase its plasticity and lower its maturing temperature. However, this clay is very durable and has a low rate of shrinkage thus making it one of the most sought after ingredients for making pottery found in the United States. We have yet to work with it ourselves but we are looking forward to the possibility of finding a native clay source with which we could supply the needs of our school and craft shop.